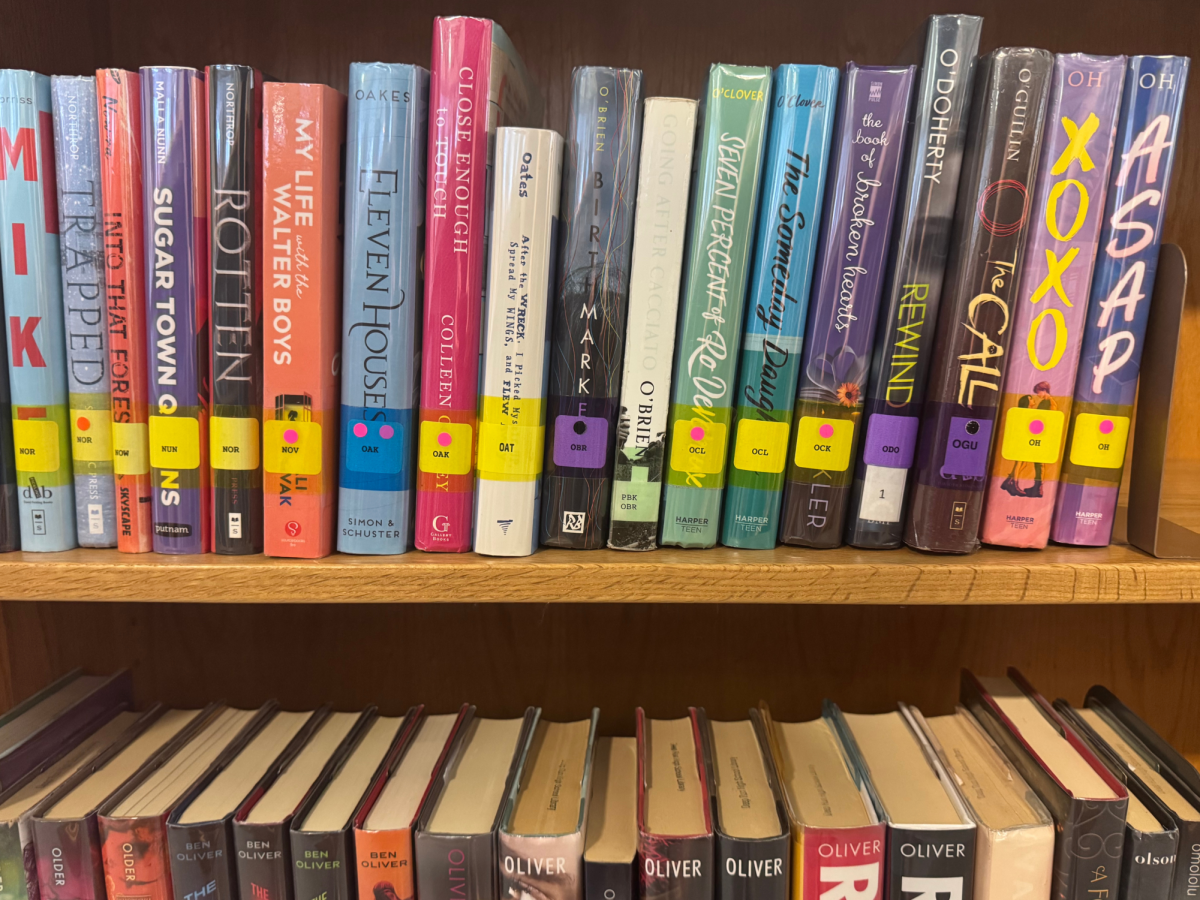

The nationwide epidemic of book censorship remains a widespread issue. Reports show that across the United States, thousands of unique titles are challenged every year by parents, advocacy groups, and even school systems themselves due to sexually explicit content, depictions of LGBTQ+ identities, racial themes, violence, and mental health topics.

Virginia ranks among the states most affected by this wave of censorship, placing fifth-highest in the nation and second-highest on the East Coast for the number of disputed titles in public schools and libraries. According to Axios, in 2023 alone, nearly 400 unique titles were challenged across the state, including modern classics such as “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” by Stephen Chbosky and “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood.

In Virginia, book-banning efforts have been primarily concentrated in counties such as Madison, Loudoun, and Hanover. However, the issue has also surfaced in Henrico County. For instance, in Jan. 2023, “Monster” by Walter Dean Myers was requested to be removed from Henrico County Public Schools (HCPS) due to its mature themes and sexual content.

In recent years, Virginia legislators have attempted to address rising public concern over the ongoing practice of book censorship but have been largely unsuccessful. Notably, in Jan. 2024, Sen. Ghazala Hashmi (D-Richmond) and Del. Karrie Delaney (D-Centreville) introduced Senate Bill 235 (SB235) and House Bill 251 (HB251), respectively.

The bills outlined several requirements for school policies, including (i) notifying parents about instructional materials containing sexually explicit content; (ii) identifying specific materials and topics considered sexually explicit; and (iii) allowing parents to review these materials and request alternative, non-explicit options for their children.

Many voters incorrectly assumed that such came from the right in an attempt to expand perceived parental rights or censor academic materials; however, that is not actually the case. The goal, Sen. Hashmi explained, was instead to “[make] clear that censorship and book bans are not to come as a result of parental notification.” Specifically, SB235 and HB251 sought to establish a framework for parental notification policies that balanced parental involvement with the protection of access to diverse educational materials.

In March 2024, Gov. Glenn Youngkin vetoed both SB235 and HB251. But even if they had been enacted, their impact likely would have been minimal.

At most schools, including Deep Run, parental notification is already standard practice. Additionally, the bills’ provisions were flimsy at best. They included no clear definition of “parental notification.” It could range from an email warning of book content to parents to providing a simple anticipated reading list on course syllabi at the start of the year. SB235 and HB571 made no such clarifications, leaving ambiguity that would make their implementation a veritable bureaucratic nightmare.

This outcome is typical when policymakers with limited expertise in education impose their preferences on the education system, especially in response to a sensitive issue like book censorship, which requires a more in-depth, firsthand examination of classroom materials.

But while the bills themselves were redundant, clunky, and unworkable in their provisions, the sentiment behind them persists: the issue of book censorship demands continued legislative attention. More creative approaches may be in order, approaches that work directly with key stakeholders. Many innovative anti-censorship initiatives in other states continue to have shown immense potential. The best practices demonstrated by these initiatives could certainly be adapted for use in Virginia.

For instance, in 2024, Illinois introduced financial incentives to discourage book bans. Libraries that fail to adopt the American Library Association’s (ALA) Library Bill of Rights or create their own written policy against book bans risk losing state grants.

Later that year, New Jersey passed a law making it illegal for schools and public libraries to ban books based on their content or the background of their authors. Additionally, Colorado legislation has focused on professional development for librarians and educators, equipping them to handle book challenges and foster open dialogue about controversial topics.

Any combination of these approaches, if implemented in Virginia, could deliver measurable results. While the epidemic of book bans must be addressed by any means necessary, SB235 and HB51 may not be the right solutions. These bills aimed to clarify existing policies and create a model for parental notification policies, but they were unnecessary given current policies and common teaching practices.